This essay intended to investigate the nuances of a nebulous artistic archetype I sensed but couldn’t define and to examine its political ramifications. This process proved far more complicated than I had hoped. How can I try a criminal when I cannot bring them to court? As such, this series must balance its political inquiries with an attempt to draw a through-line among artists who share a sensibility I have yet to articulate.

The term “outsider artist” initially inspired this pursuit. Its evolving definition has sparked new questions about inclusion and language in the art world, reconfiguring how we frame artistic legitimacy. I wanted to do the same with this inquiry. The archetype blends asceticism, metaphysical preoccupation, and obsessive focus, yet its artists span class lines and political ideologies, challenging my “historical-materialist sensibilities.” Sun Ra was the first artist I studied closely in this context—and the original inspiration behind the term “monk-artist” that I used to define this sensibility. However, near the end of the editing process, Brandon (bff and editor) noted the gendered weight of the term and urged me to dig deeper for a label free of those implications.

Though “monk-artist” captured the mix of obsessive study and ascetic devotion I was drawn to, I began to wonder whether that blend was a privilege historically afforded mostly to men. The existence of nunneries, Alice Coletrane, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, and many others proves otherwise, of course—but as with any forensically sound investigation of the relationship between material circumstances and artistic sensibilities, gender must be considered. Hopefully, this inquiry will eventually land on a single-word term that succinctly defines this archetype. But for now, the most accurate label will likely require ongoing redefinition. Hip hip hooray.

I: Sun Ra: Introducing the Monk Artist

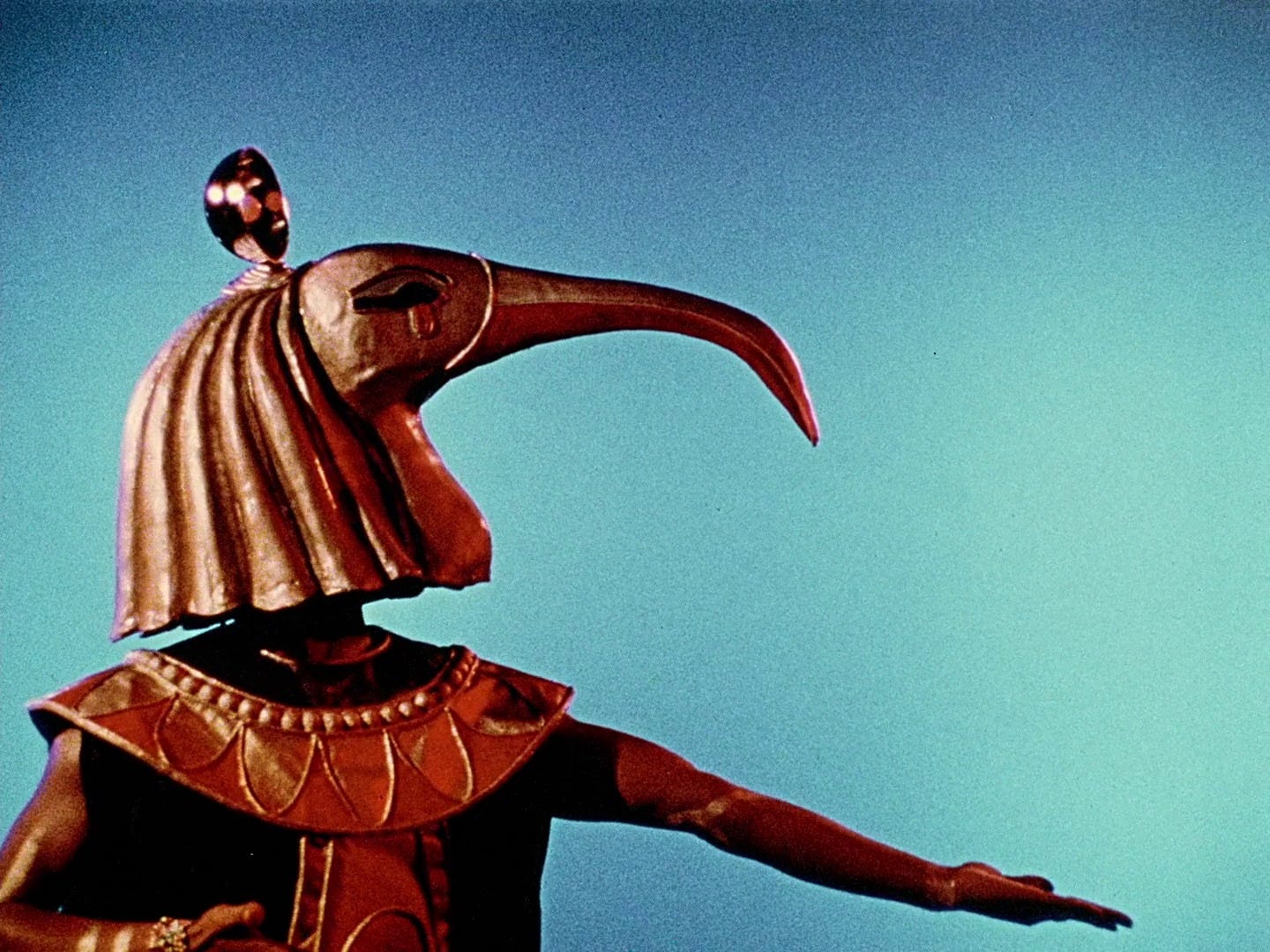

I was first introduced to Sun Ra while attending the Blackbird Academy, a small institution in Nashville, TN for education in audio engineering. My late teacher, Mark Rubel, taught the study as a combination of technical skills and a life philosophy. It was the engineer’s job to capture the divine energy of music and transfer it into the form of recorded audio. Rubel grew up in Champaign, Illinois, as a secluded, dreamer type and recalled the story of first witnessing Sun Ra as an epiphanic moment. Walking home from school one day, he stopped to watch a congregation of well-accessorized people shuffling equipment from their cars to the local jazz club. From afar, Rubel saw a golden falcon head, large enough to fit over the torso of a human being, emerge from the depths of an unassuming sedan. As the group scurried about, he was convinced this was some government agency hurriedly unloading artifacts from Area 51. Curious, Rubel inquired about the identity of the performing group, and the frenzy distilled to a simple name as the roadie uttered: “Sun Ra.”

Perhaps best known for his eccentricity, Sun Ra’s resume is (like his outfits) layered, complex, and difficult to compare. Writer, poet, director, saxophone player, keyboardist, cosmic thinker, and originator of the still-running free jazz group The Arkestra, Sun Ra used his art to spread the gospel of his religious and political philosophy. His radical spiritual beliefs and devotion to an isolated aesthetic evoke monastic life; thus, I use the imperfect term “Monk artist” to describe the archetype explored in this essay.

The “Monk artist” spends their life in devotion to their craft. Akin to the religious devotion a monk pays to studying their faith throughout the course of their life, the “Monk artist” often sacrifices some degree of material security, recognition or social stability in exchange for remaining true to the vision they present, no matter how ambitious or eccentric. This sacrifice and devotion is often accompanied by a larger philosophy or faith held by the artist. Sun Ra maintained a fervent belief in the sanctimonious capability of the cosmos. Arvo Pärt proclaimed his orthodox faith despite it leading to his exile from Soviet Russia. The late Steve Albini famously renounced royalties from his recording duties out of a strange amalgamation of punk Marxist beliefs.

Whether or not these artists remained faithful to their monkish status is not my concern. These are human beings, after all. Their prescription is based on two things: the first being their intention of monkish devotion, and the second being their public perception. If the artist themselves claims a particular devotion, they are thus ascribing to the “Monk artist” archetype. Alternatively, if they hold no loftier, spiritual motive for their work, but their public perception maintains their reputation as thus, then the artist’s lack of stated intention is overridden by the popular interpretation of their artistry and mythology in public discourse. With this criteria established, this series will aim to illuminate the relationship these "Monk artists” maintain with contemporary politics.

II: The Monk from the Moon

In Sun Ra’s 1974 conceptual album/film Space is the Place, he parks his spaceship above Oakland, CA, and battles with a devilish figure for the fate of the black community. The battle ropes in many political groups of the time: NASA attempts to kidnap Sun Ra, the social group that is a thinly veiled replica of Black Panther Party is run by a vicious pimp and all white people are nervous, sexless wrecks. While vying to uplift the human race to a higher place with his music, Sun Ra never shies from the political circumstances that stand in the way.

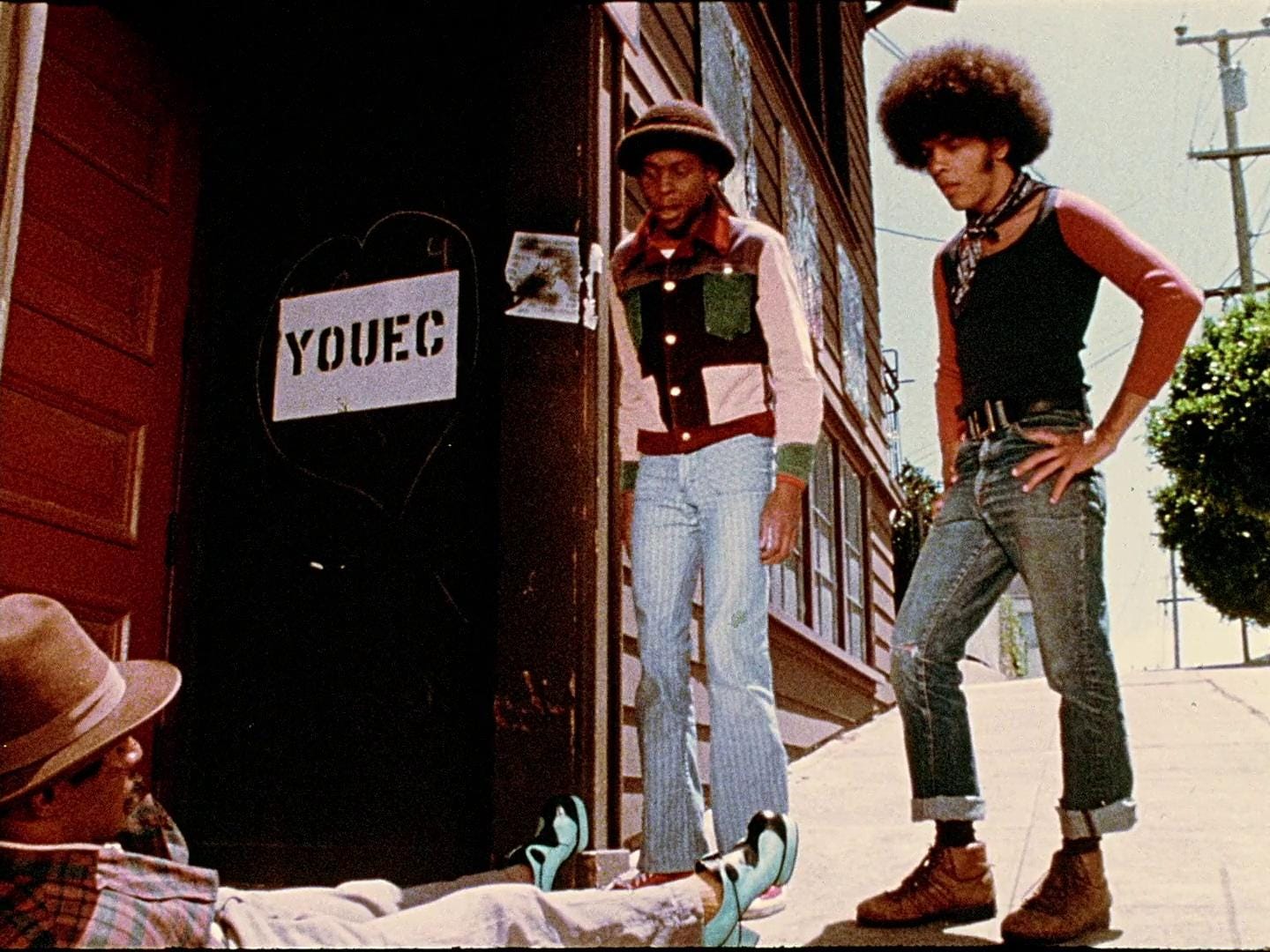

One scene begins as two characters steal shoes off a drunken man collapsed outside a social hall for Black Youth. The title above the hall reads: “Youth Development Program,” and the inside is adorned with pictures of black activists, alluding to the typical design of the Black Panther Party’s social halls. As a montage of the actions inside the building plods, the mix of innocent pastimes edges on hedonistic purgatory. Dancing, singing, pool, ping pong, card games, bubble gum chewing… these innocent actions instill anxiety in the context of the prior theft and the gratuitous endurance of the shot. The film satirizes the Panther Party, suggesting a lack of ambition and discipline. Crowded, cloistered chaos looms until Sun Ra’s synthesized, alien sound plays, coming to a halt as the camera focuses on his empty shoes, foreshadowing his apparition. Appearing in full garb, Sun Ra announces himself to the stunned crowd.

“Greetings, black youth, Planet Earth. I am Sun Ra, ambassador from the intergalactic regions of outer space.” The room falls silent and looks to Sun Ra, adorned in his trademark garb: bedazzled shoes, a hood made of golden mesh, a large cane and two flanking figures in gold masks styled after Ancient Egyptian art. Confused, the crowd meets his greetings with ridicule: “Why your shoes so big?” rings on, “Are those moon shoes?” rings another, “Are you even real?” The crowd’s digs evolve into a mocking laugh, equal in scorn to the film’s depiction of the Panther Party. Now it’s the crowd’s turn to laugh at Sun Ra.

“How do you know I’m real?” Sun Ra asks hypothetically. “I’m not real. I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. If you did, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. You not real. If you were, you’d have some status among the nations of the world. So we’re both myths. I do not come to you as the reality. I come to you as the myth. Because that’s what black people are… Myths.”

Suddenly, a justification of the prior satire emerges as Sun Ra lays his vision clear: a cosmic, futurist alternative to the Black Panther Party’s materialist aims. In 1974, the Party was at a weak point, having lost pivotal members to skirmishes with the police, suffering from infighting, corruption and counter-intelligence probes from the federal government. In this vacuum, Sun Ra takes an opportunity to launch his agenda and calls on the black youth to invest in the space race. He claims that white people are going on “frequent trips to the moon” and “not inviting” black people. Insinuating that Earth is soon to be no longer capable of holding life, Sun Ra warns that if black people wish to survive, they ought to leave Earth.

Sun Ra’s mission is, like his outfit, full of immense ambition and subject to reactionary ridicule. In the vacuum caused by the semi-collapse of the Panther Party arose a criticism that deemed the party too progressive, too disruptive, too radical. Unfazed, Sun Ra responds with a political agenda for space exploration and an aesthetic vision of free jazz, isolating himself socially and artistically.

III: Loner

A few stages define the process of adopting the “Monk artist” philosophy. The first stage is concerned with embracing isolation. At this stage, the “Monk artist” discovers that their monomaniacal focus moves them to momentary isolation, social, material, or both. But it is the hope of the artist that they will overcome this isolation and their message will be “understood.” In his plea to the crowd, Sun Ra articulates a hope that his work will change the spiritual and material well-being of black people. He understands that his costumes, rhetoric and music ostracize him, but ultimately, that ostracization will become adoration.

The next stage is more extreme, suggesting that isolation and progressive genius are coexistent. The more isolated a figure is, the greater the change spurred by their work. The “Monk artist” examines the degree to which an artist should maintain steadfast individualism as a primary factor when determining the worth of their work.

In his essay “On the Spiritual in Art,” Wassily Kandinsky succinctly lays out the requisite isolated nature of the Avant-Garde artist’s relationship to society:

“A large acute triangle divided into unequal segments, the narrowest one pointing upwards, is a schematically correct representation of spiritual life. The lower the segment the larger, wider, higher, and more embracing will be the other parts of the triangle. The entire triangle moves slowly, almost invisible, forward and upward and where the apex was ‘today,' the second segment is going to be "to-morrow, that is to say, that which today can be understood only by the apex, and which to the rest of the triangle seems an incomprehensible gibberish, tomorrow forms the true and sensitive life of the second segment. … At the apex of the top segment, sometimes one man stands entirely alone.”

As Sun Ra appears in the youth center, his outfit recalls Kandinsky’s “incomprehensible gibberish” and is only understood in the wake of his speech. He finds himself subjected to the isolation Kandinsky celebrates. Though the tone of Kandinsky’s prescription is grief-stricken, there is an undoubtable pride attached to the label of the avant-garde and isolated status. This is one of the most troublesome aspects of the “Monk artist” archetype.

Kandinsky’s dream of spiritual evolution for humanity is lofty and intangible, with no material relation articulated. Beethoven, whom Kandinsky uses as an example of spiritual genius, was patronized by wealthy courts and, by most accounts, lived a comfortable life. He was far from materially isolated. Alternatively, Sun Ra’s material circumstances directly inspire the philosophy that isolated him.

Throughout the film, Sun Ra’s cosmic paradise is promised as a salvation for black folks from their diminished material and societal status. As Sun Ra satirizes the Black Panther Party, who espouse Marxist rhetoric, he positions himself as an intellectual contender against Marxism. In the film, the antagonist pimp character gives money to homeless men, hires prostitutes for his friends and gambles fairly with the youth. He is a twisted patron, a plot device that proves Sun Ra’s belief that material pursuits only lead to corruption. Though Sun Ra’s promise is to take black people to space, his vision is more metaphorical than literal. Sun Ra’s vessel for space travel is music, an immaterial, spiritual savior, yet his intent for material change remains.

His speech to the youth offers a freedom from the demise of the earth, presenting the twofold promise of spiritual and material profit. Returning to Kandinsky’s triangle, if one were to mold their life after this model, their socially isolated status would usually manifest into immense material strain. How can you make any money without connection or social status? Sun Ra poses himself as a literal alien in the film, suggesting that the means for achieving his spiritual and material circumstances are incapable of being found on earth.

Kandinsky’s implicit celebration of isolation without regard to material circumstance reveals, graciously speaking, a weakness in his vision. More bluntly speaking, it reveals a delusional narcissism. Recognizing the vast difference in the material concerns of these two artists’ goals, yet similarly isolated status, it is a harrowing conclusion that Sun Ra’s dream of a materially and spiritually prosperous black population isolates him to the same extent that Kandinsky’s model calls for in order to inspire a spiritual reinvigoration for the human race. Kandinsky is afforded the privilege to dream of a spiritual rebirth absent of material circumstance; Sun Ra is not.

Sun Ra’s monkish devotion concerns material circumstances and socio-political relations, and his art reflects this. The film frequently places him in the face of ideological opposition, anticipating and reacting to critics of the material world, didactically justifying its isolation. As the scene plays out with Sun Ra explaining his mission to the black youth, the film thus operates as an anticipatory mechanism, posturing Sun Ra’s work to withstand the criticisms to which Sun Ra had previously faced and would continue to face. It becomes one grand artist’s statement. But as the film assumes this posturing stance, the lofty ambitions for his music face the risk of crumbling to the level of propaganda. The ambition of the free-flowing, radical sound of Sun Ra’s free jazz Arkestra suffers a discordant contrast with the more didactic elements of the film.

IV: Myth, Messiah and Money

In his royal garb, Sun Ra utters a messianic proclamation: “I come to you as myth, because that’s what black people are: myth.” This mythical status is paradoxical. It is the power that enables him to teleport into the Black Panther hall and float in a spaceship. But the word also connotes an immaterial, and in the context of Marx-influenced Panther ideology, therefore unequal status. As the word “myth” is uttered in the social hall, the truth is clear to Sun Ra. The most valiant effort to attain equal rights for black people has failed. Though the Black Panther Party fought hard, black people are still “myth.” Sun Ra suggests that, rather than seeing black people’s material inequality exclusively as a problem to solve, it ought to be used as leverage to launch black people to a higher realm, where they will attain both spiritual and material riches.

“Perhaps myth’s major paradox may be that it can mean either truth or (particularly in casual conversation) falsehood.” (Gentile, 85)

Within this paradox, Sun Ra finds a power, an elevated, tertiary position, ascendant from these poles of truth and untruth. To align with Sun Ra’s interpretation of myth relies on an implicit belief in the potential for a tertiary position, absent of materiality, but thriving through some alternate “cosmic” presence which gathers strength from its confused existence on earth. It is a powerful appeal: as Sun Ra defines black people as “myth,” this damning proclamation transforms into an angelic potential. Those willing to accept myth’s tertiary position can be saved, while those who opt for materiality are to be left on Earth and soon destroyed.

As Sun Ra explains himself to the black youth, they are quickly convinced of his worth. The hero’s journey now has followers. Simultaneously, Sun Ra acknowledges the necessity of an explanation for his eccentricity to be taken seriously. Thus, he acknowledges the necessity of material status and stability, breaking from the Kandinskian-mold of social isolation.

But if the power within black people is their mythical status, where they can freely thrive from the shackles of a material earth that is “soon to be destroyed,” why does Sun Ra lower his message to the plane of the film? If the vessel to sanctity is Sun Ra’s music, why make a movie? Thus enters the great question that Sun Ra and Kandinsky’s art inspire: If the spiritual realm is so strong, why must it be articulated?

In its anticipation of criticism, Sun Ra’s vision shrinks, revealing the inherent conflict within any attempt to elevate spiritual and material circumstances simultaneously. But, consider Sun Ra’s material circumstance, and the necessity of the act reveals itself. How is Sun Ra going to play any shows and make any money if no one understands what he’s doing?

Sun Ra’s art is an eclectic mishmash of innumerable political and religious ideals that are inconclusive without his aesthetic vessel. The choice to employ aesthetics over didactic politics suggests an implicit weakness in political strategy, yet the film takes a firm, well-defined political stance. In the film, Sun Ra’s music is the ultimate vehicle of freedom, lifting the listener to the metaphorical cosmos. Sun Ra suggests that the subjugation of Black people is a problem that arises from an inherent fault in human consciousness. Only music, not political strategy, can surmount it. So why does the film bother appealing to it? Why subject art to the inherent politics and material conflicts of the world of film and concerts? Why engage in propagandistic messaging?

Though Sun Ra’s message supposedly arose from an immaterial place, as a young Mark Rubel will attest, at the end of every Arkestra show, the head-dress comes off, goes into the trunk of a car, and travels to the next show. Even the monks need money. But is it the artist’s job to address this need? One person’s hypocrisy is another’s pragmatism.

Influence is impossible to measure, and generating a serious probe into the efficacy of Sun Ra’s attempt to elevate the material and spiritual circumstances of black people is a futile exercise. So what is the effect if the vessel in which a political and aesthetic message is carried does not align with the politics it preaches? If the vision is truly muddled down by its packaging, how strong can it be?

Alternatively, if the vision is as inspiring and as powerful as the artist deems— what use is there in preaching it? Why would it need packaging? Should it not simply reveal itself? Or is its proclamation another act of prayer? Is the true beauty of the vision manifest in the moments when the artist and the viewer align and celebrate together?

Does harmony uplift or dilute a melody?

Works Cited:

https://film-grab.com/2022/07/13/space-is-the-place/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kandinsky_-_Multi_Colored_Triangle,_1927.jpg

Gentile, John S. “Prologue: Defining Myth: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Storytelling and Myth.” Storytelling, Self, Society 7, no. 2 (2011): 85–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41949151.

Space Is the Place, Dir. John Coney, written by Sun Ra. Janus Films. 1974.

Kandinsky, Wassily On the Spiritual in Art, Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, 1964, New York City, Internet Archive,https://www.csus.edu/indiv/o/obriene/art206/onspiritualinart00kand.pdf

Such an interesting exploration, and an unexpected but ultimately logical marrying of two seemingly disparate artists. Also, oddly, I’ve both been listening to Sun Ra and reading The Spiritual in Art recently!

Amazing read. Thanks for such a thorough exploration